|

The Windemuth

|

Reunions Media Contact Us

|

A Civil War story about two Windemuth descendants.

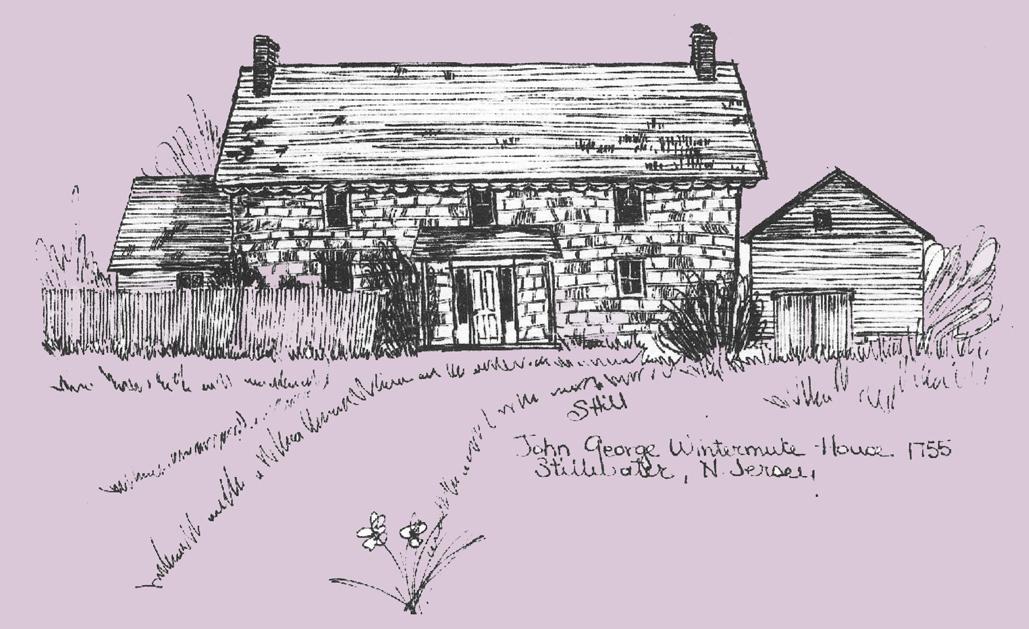

The following article is the full essay researched and written by Windemuth descendant Rachel Denise Phillips Terry of Centreville, VA. Rachel is pursuing a degree in history at George Mason University, Fairfax, VA and wrote the paper as a requirement for her Civil War History class. Her paper “A Family Civil War History of Andrew Rice Wintamute of the Pennsylvania 143rd Regiment and Aaron Hazen Wintamute of the Pennsylvania 12th Reserve Corp” has been included in the Civil War historical files at Antietam National Park and Battlefield. Her grandmother, Lois Jean (Shupp) Tiller of Lake Anna, VA, assisted Rachel in the research. A condensed version of this essay appeared in the July 2004 Windemuth Family Newsletter. Aaron Hazen and Andrew Rice Wintamute By Rachel Denise Phillips Terry The Wintermute family traces their heritage back to Johann Georg Windemuth of Germany. The progenitors of the family immigrated to the United States in the 1700s. Members of the Windemuth/Wintermute/Wintamute family have fought in every major American conflict going back to the Revolutionary War. The focus of this essay is two brothers, Aaron Hazen and Andrew Rice Wintamute. The brothers were two of the thirteen children born to Jacob Staley Wintermute and Rachel Ann Rice. Both were born in Stillwater, Sussex County, New Jersey. Aaron Hazen was born October 19, 1835, and Andrew Rice was born August 29, 1841. The family relocated to Mehoopany in Wyoming County, Pennsylvania, in the spring of 1855. Both brothers listed their occupations as farmers on their military enlistments. For an unknown reason, both brothers were in the process of changing their names, both have Wintermute and Wintamute listed on their respective records. Aaron Hazen Wintamute was twenty-five years old when he enlisted into Company B of the Twelfth Regiment Pennsylvania Reserve Infantry on May 15, 1861. He was five feet nine inches tall with a dark complexion, grey eyes, and black hair. He was enlisted by Captain J.B. Harding for a three-year term of service. This description was given on both his Regimental Descriptive Book and the Civil War Veteran’s Card File, 1861-1866 on file from the Pennsylvania State Archives. Aaron Wintamute was mustered in as a Corporal on August 10, 1861, in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The primary source for Aaron’s regimental history is Dyer’s Compendium, although it will be demonstrated (as common with many other soldiers) Corporal Wintamute was often not with his Company but detailed on other military duties. The Twelfth Regiment was commanded by Colonel John H. Taggart of Philadelphia, Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Bailey of York, and Major Peter Blady of Northampton. On August 20, they joined the Third Brigade of General McCall at Tenallytown for drills and picket duty. On October 10 the Regiment began a march into Virginia, but according to Aaron’s Company Muster Rolls, his presence or absence from August through December 31, 1861, is not stated. It is not clear if Aaron participated with his regiment in the skirmishes at Dranesville, Virginia, on December 20, 1861. Beginning in January and February of 1862, his Company Muster Rolls list him as “present” through June 1863, so it is safe to assume he was present within his Company as the Regiment took part in several battles. January through March of 1862, his regiment was stationed at Langley, where they broke camp on March 10. By March 16 the weather forced them to make camp at Falmouth, where they remained until April 19, 1862, when the regiment was detached from their division to relieve the Second Wisconsin in guarding the Orange and Alexandria Railroad, with headquarters established at Catlett’s Station and the Regiment detached along eight miles to guard the road. On May 6, 1862, the Twelfth Regiment was ordered to rejoin their division, which was now stationed at Falmouth. From there, the division, under the command of Brigadier General Truman Seymour, was ordered to join General McClellan in the Peninsula Campaign. On June 12, 1862, the Twelfth Regiment was transported down the Rappahannock River on transport ships for two days until they debarked at White House on June 14. Over subsequent days, the Regiment proceeded to New Bridge, then Ellerson’s Mill on Beaver Dam Creek where they set up camp and picket duty within sight of enemy lines. They were responsible for providing hourly bulletins to Generals Reynolds and McClellan until the Seven Days Battles commenced and another regiment took up picket duty. On the morning of June 26, 1862, the Twelfth Regiment was holding the extreme left of the line from Ellerson’s Mill to Cold Harbor. Corporal Wintamute’s Company B occupied rifle pits and a grove of trees as cover while they engaged the Confederate troops from three o’clock in the afternoon until nine o’clock that night. The regiment was ordered to maintain their position until daylight and then retire. During the next two days, they marched to Gaines’ Mill where they were placed to support Griffin’s Battery. During the next three hours, there was a tremendous battle that resulted in a loss of six men and twenty-five wounded soldiers from the Twelfth Regiment. During this time, Colonel Taggart was knocked from his horse. By June 29, the Twelfth Regiment was detailed on guard duty for the Reserve Artillery of their Brigade. It was reported to be dreadfully hot; the Regiment was forced to march over 18 miles and then was on picket duty on the James River, where they got lost. Dyer’s Compendium contains the following excerpt from Colonel Taggart’s report: The White Oak Creek, which we crossed about noon, was a complete quagmire, from the thousands of horses, teams, and artillery, which were continually passing, and water to drink was not to be had. Some of the men became almost delirious from thirst, and once, when I halted for rest a few minutes, I discovered them drinking from a stagnant puddle in which was the putrid carcass of a dead horse. Poor fellows, I pitied them, but I could not permit this, and I promised them good water at White Swamp Oak (as I was informed by an engineer officer,) but as we arrived there we found it utterly unfit to drink. The disappointment was intense; but we pushed on, and at evening, when we halted on the green, and General McCall came up and told us there was plenty of good spring water in a rivulet near by, the joy of the men knew no bounds. Alas! Little did they think that on that very spot, in less than twenty-four hours, many of them would pour out their life’s blood, and the waters of that little brook would be reddened by the vital current. Yet so it was. On June 30, the Twelfth Regiment, as ordered by General McCall to Colonel Taggart in person, took their places on the extreme left of the line at one o’clock in the afternoon. The engagement at Malvern Hill was dreadful for the Twelfth Regiment. After 24 hours of heavy combat, most of it hand to hand, the regiment was finally ordered to Harrison’s Landing, where it arrived on July 2. The total loss of the Twelfth Regiment in the Peninsula campaign was thirteen dead, sixty wounded, and thirty-six missing. As part of General Mead’s army and still led by Captain Gustin, the Twelfth occupied the center of the line, advancing on the pike leading from Frederick City to Hagerstown. This advance led to six killed and nineteen wounded. All through September 16 and 17, the Twelfth fought at the Battle of Antietam, which cost them another thirteen dead, forty-seven wounded, and four missing. After being re-supplied on the banks of the Potomac River, the Regiment continued following the retreat of Lee’s Army. Once General Burnside was appointed as commander of the Army of the Potomac, the Twelfth Regiment, still under the command of Captain Gustin, was ordered to join the division of forty-five hundred men under the command of General Mead, to attack Fredericksburg. On December 13, 1862 the Twelfth Regiment, as part of the Third Brigade, led the assault on Fredericksburg with heavy casualties and losses: thirteen dead, seventy wounded, and thirty-four taken prisoner. This is also where Aaron contracted some sort of illness that affected his lungs. Several of his comrades sent affidavits describing his illness and the fact that he didn’t recover. The next major combat for the Twelfth Regiment was Gettysburg. They had been combined into the first division of the Twenty Second Army Corp. They reported to the city of Washington in April for six weeks of provost duty. They reached the battlefield at 10am on the morning of July 2, 1863. They were ordered to the left flank of Little Round Top to the right of Hazlett’s Battery and eventually took part with the Third Brigade on the assault on Little Round Top. As far as casualties, the Twelfth only lost one man with only a couple of wounded. Aaron was reassigned to recruiting service in Philadelphia on July 26, 1863, “on detached duty in accordance with S.C. Number 156…to proceed after drafted men” by order of General Crawford. Aaron Wintamute remained on recruiting duty through the end of his term of service on June 11, 1864, when he was paid $18.03. He had $21.75 as the amount for clothing in kind or money advanced and was due $100. After being mustered out of the Army, Aaron returned home. He returned to farming and joined the Masons in 1865. By 1866 he had moved to Iowa. He married a widow Sabina Silverthorne on September 4, 1867. She had one son George C. Flanner and they later had a son together-- Edgar who was born July 2, 1868. Aaron worked in the lumber business in Iowa and then Illinois. He spent years in farming and the lumber business, although his lung condition had left him quite feeble and unable to do manual labor. In February 1890, he made his first request for a pension, which was denied. He eventually began receiving a pension October 10, 1890. He and his wife retired to Biloxi, Mississippi, where she died in 1913. Aaron Hazen Wintamute died May 8, 1919. The only record discovered so far on his death was a letter written by his stepson George Flanner to the Department of the Interior dated December 29, 1919, saying that Aaron was dead, and he was the executor of the estate. No record of Edgar has been found to date. Andrew Rice Wintamute was twenty-one years old when he enlisted in the One Hundred Forty Third Pennsylvania Regiment, Company K, of the U.S. Army at Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, on August 20, 1862. He mustered in on September 1, 1862, as a Private. He is described on his discharge papers as five feet eleven and a half inches tall, with a fair complexion, grey eyes, and brown hair. Andrew Wintamute’s Company Muster Rolls show him present with his regiment, within Company K from September 1 through June 1863. The history of the One Hundred and Forty Third was compiled by Samuel Bates. The Regiment was stationed to the northern defenses of the city of Washington from November 7 through February 17 when it was ordered to the front at Belle Plains and assigned to the Second Brigade, Third Division. They took part in the Battle of Chancellorsville May first through the sixth. They camped at Falmouth until they were ordered to Gettysburg. In Gettysburg, the 143rd was in position where the Theological Seminary stands. They later fell back and took position at Cemetery Hill. In July of 1863, he was wounded in Gettysburg on the first day of battle and was absent from duty until February of 1864. He rejoined his Regiment in March of 1864, which had been so depleted that they were reassigned to the First Brigade, First Division, Fifth Corps. Andrew Wintamute continued with them until he was killed at the Battle of Wilderness on May 5, 1864. The Fifth Corps was commanded by General Crawford, and they were positioned at Chewning Farm in support of General Warren. They were then ordered to attack across a clearing called Saunder’s Field. The word across the regiments was “Boys, label yourselves, if we must go down in there, as you will never come out again.” Private Andrew Rice Wintamute was killed “by gunshot wound while engaging the enemy.” Andrew was one of two thousand, two hundred and forty-six who died during the three days of battle. His discharge paper work was processed near Petersburg, VA, in July of 1864. Somehow, his body was transported home, and he was buried in the family plot at Union Hill Cemetery in Wyoming County, Pennsylvania. It is not yet clear how his body was claimed.

Windemuth Family Heritage 1996, Volume 2. Frederick H. Dyer, A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion Compiled and Arranged from Official Records of the Federal and Confederate Armies, Reports of the Adjutant Generals of Several States, the Army Registers, and Other Reliable Documents Des Moines, IA: The Dyer Publishing Company, 1908, as reprinted on: http://www.geocities.com/Wellesley/5372/cw143/bated.htm. Gordon C Rhea, The Battle of the Wilderness: May 5-6, 1864 Louisiana State University Press (1994), 162-166. http://www.civilwarhome.com/wilderness.htm-Source: “The Civil War Dictionary” by Mark M. Boatner III. To Link to our Facebook Page |

Webmaster | James Wintermute Template Design: Genealogy Web Creations

|

|